In considering the importance of a Christian voice in our culture, and particularly in the field of bioethics, Allen Verhey writes, “To raise a theologically articulate voice in protest or in hope may be a sign of life in the culture, and it may preserve a memory or stir an image that will make a difference to the culture.” The church is intended to be a distinctive community, living out the values of the kingdom of God and proclaiming the gospel with words and actions. The following section is intended to build the framework for a biblical understanding of some of the main issues which may impact on one’s consideration of health care and health care reform in the United States. The gospel is all-encompassing good news, which means that it has something to say about this issue. I will survey one overarching theme which is particularly pertinent—that of justice, recognizing that there is a multiplicity of approaches that can be taken and a long list of such themes that can be investigated.

a. A biblical framework

In Genesis 1:27, we read that humanity is made “in the image of God … male and female he created them.” Most scholars have concluded that “the image of God reflected in human persons is after the manner of a king who establishes statues of himself to assert his sovereign rule where the king himself cannot be present. … The image of God in the human person is a mandate of power and responsibility. But it is power exercised as God exercises power.” And as John Goldingay notes, being made in the image of God means that “humanity not only represents God but also resembles God.” Thus, it is important to understand the character of God in order that we might best represent him, resemble him, and exercise the power he has given us in the way that he exercises power. In considering the theme of this paper, I will focus on justice as central to God’s character: Yahweh is a God of justice. But what does this mean? For this, we turn to the biblical narrative.

In the Exodus story, God had to shape a people who had spent years oppressed in slavery, by the Egyptians, into a people who more ably represented—imaged—their God. Moses reminds the Israelites:

Yahweh your God is God of gods and Lord of lords, the great God, mighty and awesome, who is not partial and takes no bribe, who executes justice for the orphan and the widow, and who loves the strangers, providing them food and clothing. You shall also love the stranger, for you were strangers in the land of Egypt. (Deut. 10:17-19)

God’s justice is revealed in tangible acts; his characteristic qualities are proven only when his saving actions attest to them. And it was God’s justice that became the reason for the Israelites to do justice: “I am Yahweh your God.” This meant:

- having honest balances, honest measures, honest practices, because Yahweh their God is an honest God (Lev. 19:36; Deut. 25:15; Ezek. 45:10);

- practicing the year of Jubilee, a year of emancipation and restoration, because Yahweh their God had emancipated them from slavery in Egypt and restored them to the land he had promised their ancestors (Lev. 25);

- loving their neighbors as themselves because love was central to Yahweh their God’s being (Lev. 19:18);

- loving the alien and the stranger among them because Yahweh their God had brought them from a place where they themselves had been aliens and strangers (Lev. 19:33-34).

Similarly in the Psalms, God’s righteousness and justice (two concepts which are virtually interchangeable from an Old Testament perspective) are not intangible characteristics. Instead, they are revealed most often in God’s saving, righteous and just actions (Ps. 71:1-2, 15-19, 21-24a). The psalmists were especially vocal in their affirmation of God’s justice, singing, “Yahweh loves justice; he will not forsake his faithful ones” (Ps. 37:28) and “Yahweh works vindication and justice for all who are oppressed” (Ps. 103:6). He is worshiped as the God:

- who helps the victim and the fatherless (Ps. 10:14);

- whose throne is built upon righteousness and justice (Ps. 89:14);

- who executes justice for the oppressed, sets the prisoners free, opens the eyes of the blind, lifts up those who are bowed down, watches over the strangers, and upholds the orphan and the widow (Ps. 146:5-9).

Yahweh is the God who commands his people, “Give justice to the weak and the orphan; maintain the right of the lowly and the destitute. Rescue the weak and the needy; deliver them from the hand of the wicked” (Ps. 82:3-4).

When his people failed to discharge their responsibilities as representatives of God and ambassadors for his justice, he raised up prophets to point this out to them:

- Jeremiah pleaded with King Shallum, “Did not your father eat and drink and do justice and righteousness? Then it was well with him. He judged the cause of the poor and needy; then it was well. Is not this to know me? says Yahweh” (22:16);

- Ezekiel spoke out against corruption, where “the alien residing within you suffers extortion; the orphan and the widow are wronged in you … you have forgotten me, says the Lord God” (22:7, 12);

- Through Amos, God denounced worship devoid of justice: “Take away from me the noise of your songs; I will not listen to the melody of your harps. But let justice roll down like waters, and righteousness like an everflowing stream” (5:23-24);

- Micah reminded the people, “He has told you, O mortal, what is good; and what does Yahweh require of you but to do justice, and to love kindness, and to walk humbly with your God?” (6:8);

- Through Isaiah, God’s words to his people are most revealing:

Is not this the fast that I choose: to loose the bonds of injustice, to undo the thongs of the yoke, to let the oppressed go free, and to break every yoke? Is it not to share your bread with the hungry, and bring the homeless poor into your house; when you see the naked, to cover them, and not to hide yourself from your own kin?

Then your light shall break forth like the dawn, and your healing shall spring up quickly; your vindicator shall go before you, the glory of the LORD shall be your rear guard. Then you shall call, and the LORD will answer; you shall cry for help, and he will say, Here I am.

If you remove the yoke from among you, the pointing of the finger, the speaking of evil, if you offer your food to the hungry and satisfy the needs of the afflicted, then your light shall rise in the darkness and your gloom be like the noonday. (58:6-10)

It is in Jesus, though, that we find the fullest expression of God’s image, and consequently, the truest paradigm for us to follow. In Jesus, we find the fullness of God and his justice embodied in a human being (Col. 2:9). Jesus took upon himself the mantle of the Servant about whom Isaiah prophesied, anointed “to bring good news to the poor, to proclaim release to the captives and recovery of sight to the blind, to let the oppressed go free, to proclaim the year of the Lord’s favor” (Luke 4:18-19; cf. Is. 61:8). Yet Jesus was also characterized by love. He commanded his followers:

- to love one another as he loved them (John 13:34, 15:12);

- to love not only their neighbors but also their enemies (Matt. 5:43);

- to feed the hungry, to give drink to the thirsty, to welcome the stranger, to clothe the naked, to take care of the sick, to visit those in prison, for “just as you did it to one of the least of these who are members of my family, you did it to me” (Matt. 25:31-46).

In all of these instructions, Jesus was seeking actions that demonstrated characteristics. Justice, I would suggest, is the effective action that makes the characteristic quality of love tangible. As the Apostle John asked, “How does God’s love abide in anyone who has the world’s goods and sees a brother or sister in need and yet refuses help? Little children, let us love, not in word or speech, but in truth and action” (1 John 3:16-18).

Catholic theologian Walter Burghardt summarizes New Testament justice:

Love as Jesus loved. The kind of love that impelled God’s unique Son to wear our flesh; to be born of a woman as we are born; to thirst and tire as we do; to respond with compassion to a hungry crowd, the bereavement of a mother, the sorrow of a sinful woman; to weep over a dead friend and a hostile city; to spend himself especially for the bedeviled and the bewildered, the poverty-stricken and the marginalized; to die in exquisite agony so that others might come to life.

Jesus is God incarnate, and in him, we see the personification of the justice, compelled by love, that is evidenced throughout Scripture as a central characteristic of God. Consequently, as human beings created in the image of God—created to image and represent God—we are called to be just people and to do justice, motivated by love and by the example of Christ. Just how this works itself out with regard to health care and health care reform, we will see a little later on.

b. A Catholic perspective

The Catholic Church has been a consistent and outspoken voice on matters of justice, particularly in addressing biblical implications for culture with a constancy that the Protestant Church has been sorely lacking. For this reason, it is instructive to look at some of the texts in which the Catholic Church has addressed the issue of health care, applying biblical teaching to a contemporary cultural issue:

- Pope Leo XIII in Rerum Novarum, published in 1891, highlighted the importance of social justice to the individual and to a peaceful society by emphasizing the importance of themes such as the centrality of the common good and its promotion.

- In 1981, the U.S. Bishops issued a letter addressing the health care problem, which restated the Catholic Church’s position and is worth quoting at length:

Every person has a basic right to adequate health care. This right flows from the sanctity of human life and the dignity that belongs to all human persons, who are made in the image of God. It implies that access to health care which is necessary and suitable for the proper development and maintenance of life must be provided for all people regardless of income, social or legal status. Special attention should be given to meeting the basic health needs of the poor. With increasingly limited resources in the economy, it is the basic rights of the poor that are frequently threatened first. …

The benefits provided in a national health care policy should be sufficient to maintain and promote good health as well as to treat disease and disability. Emphasis should be placed on the promotion of health, the prevention of disease and the protection against environmental and other hazards to physical and mental health. …

Health planning is an essential element in the development of an effective and coordinated health system. Public policy should ensure that uniform standards are part of the health care delivery system. …

Following these principles and on our belief in health care as a basic human right, we call for the development of a national health insurance program.

- In 1993, the U.S. Bishops issued a resolution on health care, restating the basic right of every human being “to adequate health care. This right flows from the sanctity of human life and the dignity that belongs to all human persons, who are made in the image of God.” This right is rooted in the sanctity of human life, and “the biblical call to heal the sick and to serve ‘the least of these,’ the priorities of social justice and the common good,” the “virtue of solidarity,” and “the option for the poor and vulnerable.”

- In the same resolution, they also laid out the criteria for reform, consistent with the principles the Catholic Church has always sought to champion:

Respect for Life. Whether it preserves and enhances the sanctity and dignity of human life from conception to natural death.

Priority Concern for the Poor. Whether it gives special priority to meeting the most pressing health care needs of the poor and undeserved, ensuring that they receive quality health services.

Universal Access. Whether it provides ready universal access to comprehensive health care for every person living in the United States.

Comprehensive Benefits. Whether it provides comprehensive benefits sufficient to maintain and promote good health, to provide preventive care, to treat disease, injury, and disability appropriately and to care for persons who are chronically ill or dying.

Pluralism. Whether it allows and encourages the involvement of the public and private sectors, including the voluntary, religious, and non-profit sectors, in the delivery of care and services; and whether it ensures respect for religious and ethical values in the delivery of health care for consumers and for individual and institutional providers.

Quality. Whether it promotes the development of processes and standards that will help to achieve quality and equity in health services, in the training of providers, and in the informed participation of consumers in decision making on health care.

Cost Containment and Controls. Whether it creates effective cost containment measures that reduce waste, inefficiency, and unnecessary care; measures that control rising costs of competition, commercialism, and administration; and measures that provide incentives to individuals and providers for effective and economical use of limited resources.

Equitable Financing. Whether it ensures society’s obligation to finance universal access to comprehensive health care in an equitable fashion, based on ability to pay; and whether proposed cost-sharing arrangements are designed to avoid creating barriers to effective care for the poor and vulnerable.

The Catholic approach to applying biblical values to contemporary issues like the one of health care is enormously helpful and instructive, particularly for an introduction such as this project.

c. Health care and the Bible: other things to consider

Building upon the Catholic perspective and drawing upon the biblical framework of justice, we may also consider the following points:

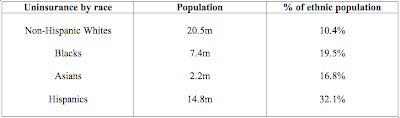

- When we consider that all of humankind is created in the image of God, what does it mean that tens of millions people in the United States are uninsured? Ron Sider concludes bluntly, “By tolerating a situation in which over 45 million people lack health insurance, this society stands in blatant defiance of God’s will.”

- When we consider that Jesus loved, welcomed, and commended children (Mark 10:13-16; Luke 18:16), what does it mean that 13.3 million American children under 18 live in poverty?

- When we consider that God shows favor to the poor, if not holding a preferential option for them, what does it mean that the poverty rate stands at 12.5% of the population, an estimated 37.3 million people, and that most of these are uninsured?

- When we consider that “those who oppress the poor insult their Maker” (Prov. 14:31; 17:5), what does it mean that the Medicaid budget, which covers hospitalization, doctors and drugs (in some states) for the poor, and provided for about 52 million people in 2004, was cut significantly by Congress in 2006?

- When we consider that Christians defend the family, what does it mean that poor families suffer doubly from being in poverty and being uninsured? When we consider that Christians value life as a gift from God, what does it mean that millions of babies born into poverty lack decent health care? “How can any Christian read what the Bible says about the poor and what Jesus says about the sick without hearing a divine call to demand that every person in this nation, starting with the poor, have access to health insurance?”

In considering our Christian role in addressing health care and health care reform in the U.S., we must be realistic, recognizing that we live in a broken and sin-marred world with broken and sin-marred people and broken and sin-marred systems. But this should not deter is from doing what we must in living up to our calling as images, ambassadors and representatives, of God. As Laurie Zoloth-Dorfman puts it:

Our discussion of health care has a prophetic responsibility. It must move beyond that which is and point to that which ought to be. …

The outcome of the national debate over health care reform will represent a compromise, the result of victories and defeats along the road to justice. But the plan itself must clearly reflect the prophetic “ought,” and it must provide a mechanism for truly democratic participation of all of us in the process of determining its final makeup. It will fail if it does not frame the issues in terms that remind us that we are part of a larger moral community, and that to do justice means to pay careful and sustained attention to the fact that people live among, are responsible for, and are obligated to others.

U.S. Bishops, “Resolution on Health Care Reform,” Origins 23 no. 7 (1993), 99-100.

U.S. Bishops, “Resolution on Health Care Reform,” Origins 23 no. 7 (1993), 99-100.